Interview with Jennifer Linggi, Illustrator / Researcher

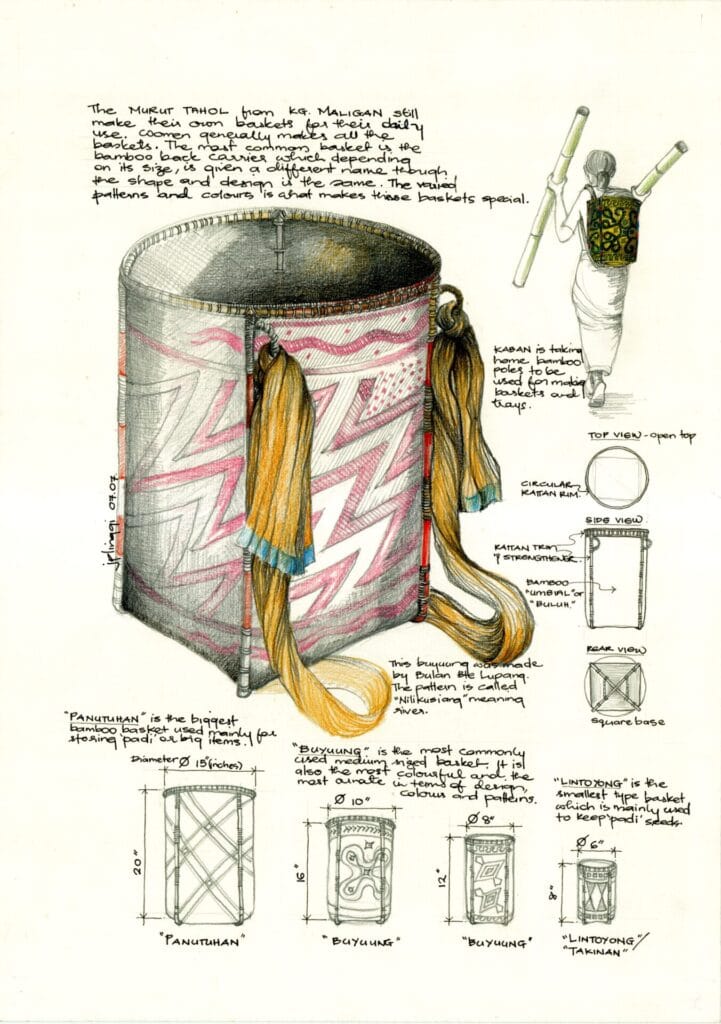

In Sabah, traditional baskets are woven by hand by the people using rattan, bamboo, and other plants found in the rich jungles of Borneo, and have been used for hunting, farming, and other daily activities. The shapes and designs are surprisingly diverse, with sizes and shapes differing greatly depending on the purpose. Jennifer Linggi, an illustrator/researcher who has traveled to villages all over Sabah, drawing sketches of baskets and interviewing the makers, tells us interesting episodes related to baskets.

Attracted by the traditional crafts of the hometown she had left for 20 years

Jennifer Linggi, from Sabah, moved to the UK at the age of 18 and spent 8 years as a student, followed by another 12 years working in architecture in Brunei, where Sabah has a neighboring border.

Returning to her hometown of Sabah after more than 20 years, she became interested in traditional crafts, but found that books and other materials related to crafts were very limited, so Jennifer herself decided to start illustrating for the record while visiting villages all over Sabah. As she interviewed people, she realized the need for research due to the lack of successors to the basket-making craft and the lack of properly documented information, and she conducted full-scale research over a period of 10 years.

Baskets essential for daily life

— I see that traditional baskets vary greatly in size and shape depending on their usage.

Baskets have traditionally been used to carry things. This is mainly for rice farming. Small baskets used to carry rice seeds are used for planting rice seeds. Very large baskets are used for harvesting. Others are used to carry daily items.

Men who go hunting in the jungle carry smaller baskets. In the past, when headhunting was practiced during inter-village wars, men used baskets to hold the heads they hunted. Women, on the other hand, carry very large baskets to carry vegetables, fruits, and grains harvested in the fields. In the sketches, I also depicted people using the baskets to show the size of the baskets.

Scaled basket for rice cultivation

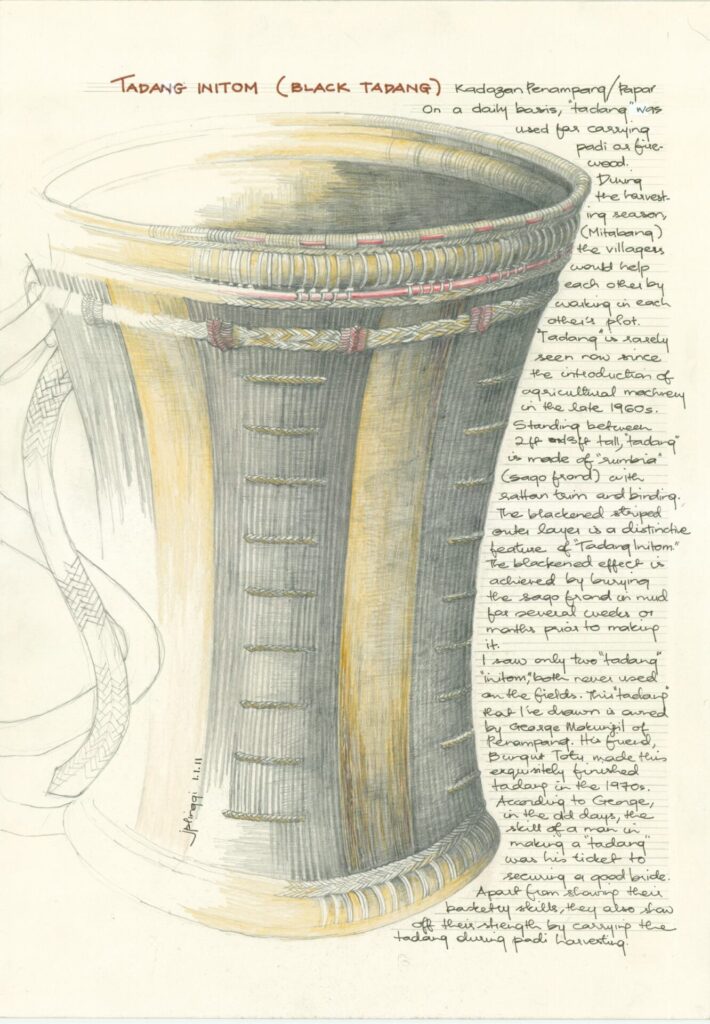

— Can you give us an example of a basket with specific features for different uses?

Rice farming, which flourished until around the 1970s, has declined in recent years, and some baskets have been lost. This large basket is no longer in use, but it was very beautiful. When I first saw some horizontal lines on the body of the basket, I thought they were just decoration. But in fact, these lines are scales for measuring the amount of rice.

One line is one gantang. A ‘gantang‘ is a unit of quantity, and one gantang is about 3.6 kilograms, or about 14 cups of a can of condensed milk (500g). It is a very clever way of measuring. For example, suppose we help each other during harvest time. If you come to help me in my rice field and bring home 10 gantangs of rice, I will bring home the same amount of rice when I go to help you in your rice field.

Collection and processing of basket materials, and weaving techniques

— Bamboo, rattan, and other local natural materials are used to make baskets. The basket-making process begins with the gathering of the materials, followed by processing and coloring, before the weaving process can finally begin.

During my research, I have accompanied people to collect bamboo for use as a material. It took us two or three hours to climb the mountain and collect the bamboo near the top, and then two and a half hours to descend the mountain carrying the bamboo with us. I didn’t carry any bamboo or rattan, I just walked down the mountain, but I was really exhausted. Thus, collecting materials is a full day’s work.

Bamboo collection on the night of the new moon

Bamboo harvesting takes place on the night of the new moon. Since it is said that a day when the moon is out is not a good day for collecting, we searched for the scientific basis for this and found that on a full moon day, the glucose content in the bamboo increases and insects come for the glucose in the bamboo. Therefore, if bamboo is cut on a full moon day, insects will remain in the bamboo. On the other hand, bamboo cut on the day of the new moon is drier, less likely to attract insects, and is said to last longer.

After a day of collecting bamboo in the jungle, the bamboo is brought back, thinly stripped, processed, and colored. For coloring, empty cans are heated from below by candlelight or alcohol lamps, and the soot that forms inside is mixed with tree liquid over several hours to create the color. Then, using the belly of the fingers, they apply it to the bamboo. I always wonder why they don’t use a brush, but they say that if you use this traditional method of coloring, the color will not fade for a long time. Of course, nowadays commercial paints and colors are also used.

Rattan canes are full of thorns

Rattan canes are covered with very sharp thorns. When collecting rattan, the thorns are removed by scraping the cane on the trunk of the tree by pulling on it. First, you need to have the skill to collect the rattan. Then, the collected rattan is boiled in mud water. The rattan process is complicated, but it is one of the strongest materials and can last up to 100 years. That is why I always tell people to stop buying brand-name bags. They don’t last long anyway (laughs). Rattan bags will last 100 years.

Motifs woven into the basket

— There are various shapes of basket motifs, is there any meaning behind them?

Motifs include simple plant motifs such as banana flowers and fruits, as well as sea fish and humans. Motifs that look human with hands, feet, and a head can also look like bats when viewed from a different angle. Depending on where you focus your view, the appearance of the motif changes, making it a very sophisticated design.

In Sarawak, also on the island of Borneo, traditional crafts sometimes incorporate symbolic creatures in their designs, such as hornbills and dragons, but I don’t think there are any symbolic/sacred animals in Sabah. I have asked many people and have heard of very few baskets with animal motifs. If there are, they are crabs, fish, or snakes. But that is also rare; the line that looks like a snake, they say, is a river. In Sabah, plants seem to be chosen rather than animals as the subject of motifs.

There is also a story of a woman who broke up a marriage by delivering a basket woven with a special motif to the man’s mother. A woman who was offered to marry a man from another village apparently did not want to marry him but could not say “no” to her parents, so she made a basket with a motif that no one had ever seen before and delivered it to the man’s mother. When the mother received the basket, she saw the pattern on it, realized that something was wrong, and went to the woman’s house to see her. This is how she got out of this marriage. I wonder what the patterns looked like.

It is not a basket, but there are also motifs that have some kind of sign or message. When people go hunting in the jungle and encounter wild animals such as wild boars or snakes, they would draw a motif on the trunk of a tree to warn their companions who would come after them of the danger.

The technique of weaving motifs is unexplainable.

And the technique of weaving the motifs is the most amazing and wonderful skill. The technique of weaving a design into a basket without a rough sketch is something that cannot be explained even by the weaver themselves. The basket is always woven from the bottom. It takes a special skill to insert the motifs on a flat surface and to make sure that the patterns are perfectly joined at the edges.

One day, I found a basket that was slightly wider than the usual narrow basket and asked the woman who made it. And the lady replied, “I’m sorry! The edges didn’t fit together properly and the shape was distorted,” she said. We are used to designing on a flat surface (2D). For example, when we do cross-stitch, we have to calculate the number of squares. But when you make a basket, you have to do the math in your head, and the edges and the whole thing has to fit together perfectly. On top of that, you also weave in the motifs. This is truly a genius skill!

Fostering the Next Generation as Successors

— Many of the traditional baskets that were essential to daily life have already been lost. What do you think is needed to continue the art of basket making in the future?

Currently, only a few people are able to make traditional baskets, but in Keningau, a town in the interior of Sabah, young people, mainly in their 30s, are working with the community to make some modern baskets. I am very happy because making modern baskets using the traditional methods will lead to the revival of the basket industry. In order to keep this industry going, we first need more people to learn the art of basket making.

I have drawn over 80 baskets for my book so far, but some of the types have already vanished, and I fear that another 80 to 90% will be lost over the next decade. In my research, I looked at what the baskets meant to the people and how they were used. I documented the dimensions, characteristics, and materials of each basket, as well as people’s beliefs about the baskets. I hope that my drawings and information will be of use to those who wish to reproduce baskets whose makers are no longer around.

It is also important to increase the number of entrepreneurs who sell baskets at a fair price. Today, baskets are sold at very low prices, but basket makers should charge a much higher price considering the skills they have acquired over a lifetime, 20 to 40 years at the shortest, and the actual process of making them. I hope that this traditional craft will be revitalized by having the makers themselves understand that the baskets are worth that much and reflect this in the price, and by developing their business through the sale of the baskets.

[Book information]

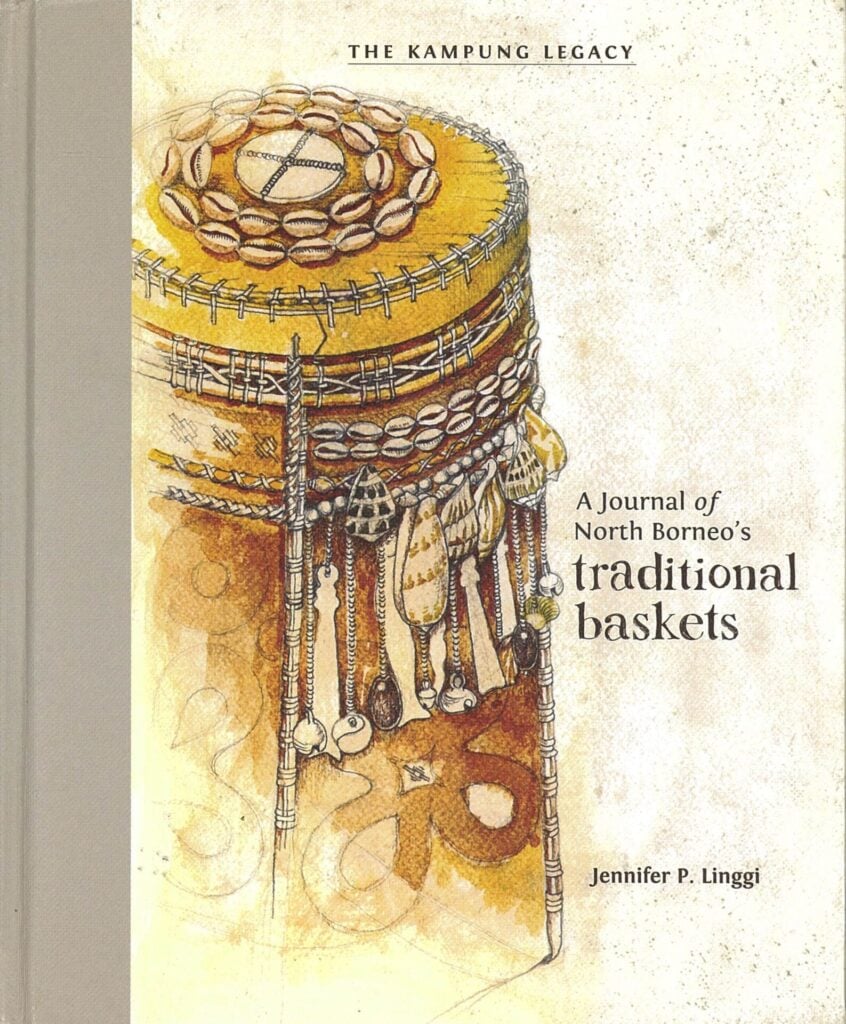

■ Jennifer Linggi 著『The Kampung Legacy – A Journal of Sabah’s Traditional Baskets』(2017)

In 2017, Jennifer published a book of drawings and information she collected and sketched over the course of 10 years. It is a valuable ethnography of different ethnic groups living in Sabah, with sketches and photographs documenting in detail their lifestyle, the use of more than 60 different baskets, each with its own name, size, basket material, processing, shape, and design, and more.

The baskets used by high ranking shamans are decorated with many shells, and there is a difference in status in the baskets. The basket used in the ritual is considered to contain spirit and energy and cannot be given away to outsiders, so the basket on the book cover is a special one that was made by a shaman for Jennifer.

Translated with www.DeepL.com/Translator (free version)

Available at Sabah Art Gallery, ILHAM Gallery (KL), Lit Books, etc.

[Exhibition Information]

■ “BAKUL: Everyday Baskets from Sabah”

An exhibition showcasing Jennifer Linggi’s collection of traditional Sabah baskets is currently being held in Kuala Lumpur.

Venue: The Godown, 11 Lorong Ampang, Off Jalan Bukit Nanas 50450, Kuala Lumpur

From the 7th Jan – 23rd Feb 2023

For more information about the exhibition: https://www.thegodown.com.my/bakulexhibition